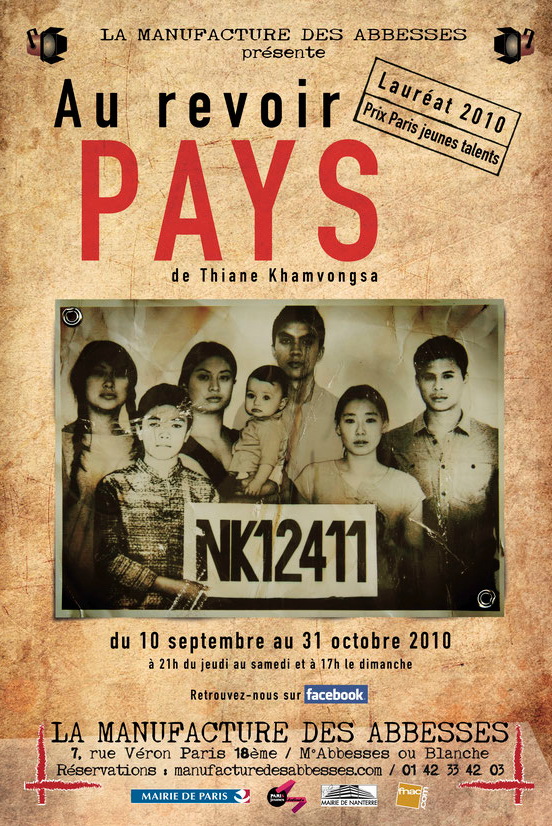

Author & director - Thiane Khamvongsa

Assistant directors - Sophie O'Byrne & Charlotte Brédy

Lights - Valentine

Music - Simon Benita

Comedians

Somphone (the father) - Jean Laurent Bourel / Mathias Mgard

Khantamaly (the mother) - Thiane Khamvongsa

Sonxhai (the eldest son) – Fred Aklan

Manila (eldest daughter) – Nabi Shin

Khosone (the youngest son) - Martin Nikonoff

The oppressors - Sébastien de Monbrison / Hugo Richet

The exploiters of human misery - Sophie O'Byrne

The French Administration - Charlotte Brédy

*****

With the support of the Paris City Hall, the Nanterre City Hall, the DDJS and Envie d’Agir.

Finding your voice again to fight against forgetting

The war in Laos tends to be forgotten by history. We know more about the fate of its big brothers, Vietnam and Cambodia. However, this small country experienced dark events in the 1970s. The civil war and the revolution will in fact lead to the exodus of nearly 10% of its population, forced to abandon everything to rebuild elsewhere. So many personal tragedies that witnesses of this era no longer wish to discuss. But how can we find peace if we refuse to heal the wounds of the past? The stories we don't tell are forever forgotten...

The author, herself from a family of Laotian political refugees, discovered the circumstances of her arrival in France by chance, during a conversation. It then seemed necessary to carry out memory work in order to lift the veil on 35 years of silence.

Identity & integration

Through his testimony, the author wanted to highlight a problem: the difficulty of recreating a feeling of belonging to a land when living in an adopted country. Indeed, by fleeing their country, refugees become stateless, they are citizens of the world… and of nowhere. At a time when a debate on national identity is being launched in France and we are talking about migrants with figures, the play challenges the viewer on themes that are more current than ever: How to define the psychological state but also the social and political positions of a person who left their homeland for a (hopefully) better life? How to manage the social constraints specific to the host country? And in general, how can we know who we really are if we don’t know where we come from?

The notions of identity and integration are closely linked but sometimes remain poorly defined... When can we say that we are French? Does this involve mastering the language? By the degree of mixing on his face? By personal recognition of what we are? By that of others? Where does integration end and assimilation begin?

In the case of Asian youth, we wrongly think that they have found their place in French society because of their economic integration. In Latin integrare means to renew, to make whole, to enter into a whole. Also, what about social integration? The first generations arrived with the desire to adapt to the host country, while nourishing the hope of passing on the culture of the country of origin to their children. The latter therefore find themselves torn between the system of values instilled in the family and the local way of life, with a permanent feeling of denying one when they comply with the other.

Les Bêtes sur la Lune

Les Bêtes sur la Lune